Dag 1: Ethnographic collections, aspects of research, preservation and conservation | Summer school

De Summer School ging van start met een introductie door Caroline van der Star, docent Studio CR Steen aan de Universiteit van Antwerpen, onmiddellijk gevolgd door Nicole Gesché-Koning, ereprofessor aan de Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten Brussel. Zij gaf ons een eerste idee over de complexiteit van etnografische collecties.

Complexe collecties

Tijdens de koloniale periode kende de kunstmarkt van etnografische objecten die uitsluitend omwille van hun artistieke aspecten werden geïmporteerd een sterke bloei. De Europese kunst werd sterk beïnvloed door Afrikaanse voorbeelden en had vooral een artistieke, esthetische waarde. Later wonnen ook technische en historische waarden aan belang. Sociale waarden liet men vaak links liggen, wat een groot verschil is met Afrika en Azië. Ondertussen vormt ook dit sociale systeem, met aandacht voor de mens achter de objecten, een belangrijke waarde in de Westerse wereld.

Door een gebrek aan kennis over en verkeerde interpretaties van etnografische objecten in Europa, worden spirituele of symbolische waarden misbegrepen of worden objecten volledig uit hun context gehaald. Hierdoor gaat de identiteit van een object verloren en wordt de integriteit beschadigd.

In een hypergespecialiseerde en geglobaliseerde wereld is het een uitdaging om te reflecteren op culturele waarden, en dan vooral de rol van erfgoed in samenlevingen die zoeken naar hun identiteit, het stimuleren om erfgoed op een meervoudige manier te benaderen, het confronteren van de theorie tegenover de praktijk, en de samenwerkingen met diverse gemeenschappen.

"Laten we nooit vergeten dat we objecten bewaren om de boodschap die ze bevatten te beschermen en hen aan het publiek te presenteren."

Gaël de Guichen, speciale adviseur bij de directeur-generaal van ICCROM

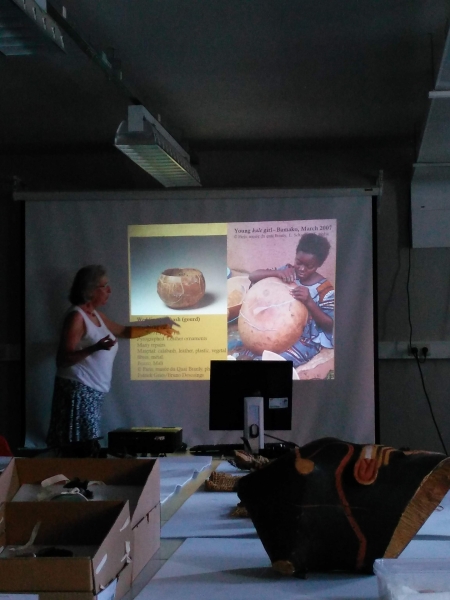

Nicole ging hierna over naar de conservatie-restauratie in Afrika. Typisch voor Afrikaanse kunst zijn de grote variaties van materialen waaruit een object kan bestaan, wat een grote uitdaging kan zijn.

Hierna legde ze het onderscheid uit tussen reparatie en restauratie. Een reparatie is een ingreep die gemaakt werd tijdens het gebruik van het object, toen het object zich nog in zijn context bevond. Ondertussen weten we dat een restauratie een ingreep is voor de preservatie van een (museum)object. Een restauratie-ingreep voegt geen extra waarde toe aan de betekenis van het object, maar een reparatie des te meer. De aanpak in het Westen verschilt van die in de rest van de wereld. Denk maar aan de bekende Japanse reparaties, Kintsugi, goudreparaties op keramiek, die meer waarde en soliditeit aan het object gaven. Het repareren is een techniek die vakkundig werd (wordt) uitgevoerd door enkel de persoon die hiervoor werd (wordt) uitgekozen.

Een ander fenomeen in Afrika zijn objecten die gemaakt zijn om maar tijdelijk te bestaan, zoals begrafenisbeeldjes. Dit gegeven staat haaks op het zolang mogelijk proberen te bewaren van een (museum)object. Het is belangrijk om met de gemeenschap te communiceren over het belang om objecten te bewaren die ook voor de volgende generaties belangrijk en leerzaam kunnen zijn, maar ook te luisteren naar hun visies.

In het algemeen is de Westerse aanpak van conservatie-restauratie niet echt bekend in Afrika. Er zijn wel een aantal opleidingen voor conservatie-restauratie, maar heel weinig.

Tastbaar erfgoed presenteren met aandacht voor het immateriële

In 1992 lanceerde de eerste niet-Europese president van ICOM, Alpha Oumar Konaré, 'Welk museum voor Afrika?’. Daarop werd, in 1994, het NARA-document over authenticiteit gepresenteerd. In 2004 volgde de declaratie van Seoel over immaterieel erfgoed, in 2006 gevolgd door de ‘Code of ethics for museums and cultural centres’ en de ontwikkeling van het begrip 'participatief erfgoed'.

Na deze historische schets gaf Nicole uitdagingen die westerse musea ervaren bij het tentoonstellen van objecten. Voor het achterhalen en exposeren van de context en de historiek van een object kan via missionaire archieven veel informatie teruggevonden worden. Maar deze informatie klopt niet altijd. Bovendien moet dergelijk fotomateriaal altijd met een kritische blik worden bekeken. Vaak waren deze foto’s geposeerd en in scène gezet. Dit geldt ook voor video's. Rituelen veranderen en video’s die gemaakt werden voor een tentoonstelling zijn soms een re-enactment van een ritueel. Desalniettemin zijn deze opnames bijzonder waardevol als weergave van het denken van die tijd.

Een tweede grote uitdaging voor musea is restitutie. Er volgde een mooi voorbeeld uit Zweden. De Haislastam ontdekte in 1991 een totempaal van hun voorouders in het Etnografisch Museum van Stockholm. De totempaal was vanaf 1929 onderdeel van het museum. Het museum kwam met de Haislastam overeen dat de oorspronkelijke totempaal teruggegeven werd aan de oorspronkelijke eigenaars. Met behulp van de oorspronkelijke technieken werd door de leden van de Haislastam een replica gemaakt voor het museum: een win-winsituatie voor beide partijen.

Enkele voorbeelden van musea in Afrika

Het Adjarra Museum in Benin was ooit een oude school. Een antiekhandelaar die zijn erfgoed verkocht en ontnam van de lokale gemeenschappen, werd curator van het museum. Het werd een museum gemaakt door de lokale bevolking voor de lokale bevolking. Een andere museum is 'Zebra on Wheels'. Doordat het voor lokale gemeenschappen zeer moeilijk is om naar een stad te trekken om er een museum te bezoeken, werd een museum op wielen gemaakt. Het museum trekt rond en houdt steeds gedurende drie weken halt op een bepaalde plaats.

Enkele interessante boeken en websites die Nicole als tips gaf tijdens haar lezing:

- Gaetano Speranza, Objects blessés. La réparation en Afrique, exposition Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 19 juin - 16 septembre 2007. Paris, Musée du Quai Branly, 2007.

- Place du Patrimoine culturel matériel et immatériel de la République Démocratique du Congo sur les Listes du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO, http://whc.unesco.org

- Cultural heritage and local development. A guide for African local governments, http://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/25/

- www.africom.museum/africom-fr./resources/books.html (AFRICOM)

- www.ceroart.org (Conserver, restaurer. Ecrire le temps en Afrique)

Korte sessies

Olivier Schalm, docent Chemie aan de Universiteit van Antwerpen, gaf een lezing over de rol van chemie bij het kunnen beoordelen en het maken van gefundeerde beslissingen in een conservatieproces. Hij startte met de levenscyclus van erfgoed en het belang van preventieve conservatie. Hij gaf de verschillende taken als problemen oplossen, beoordelen, beslissingen nemen en actie ondernemen weer en stelde in vraag of deze intuïtief of rationeel zijn.

Een conservator-restaurator kan, op intuïtieve wijze, gefundeerde beslissingen maken door de nodige training en expertise. Een chemicus is getraind om taken uit te voeren door analyses te gebruiken. Beiden hebben een verschil in aanpak maar kunnen elkaar versterken bij het nemen van beslissingen. Schalm gaf een voorbeeld van een chemische analyse, grafieken die je nog zelf moet interpreteren, en hierna de omzetting naar kleurcodes waarbij er dus een duidelijk oordeel wordt gesteld. Dergelijke kleurcodes zijn makkelijker te lezen. Ze geven de mogelijkheid om eenvoudiger te kunnen beoordelen. Voor een dergelijk systeem is het wel van zeer groot belang om vooraf te bepalen welke richtlijnen of parameters worden gebruikt.

Hierna gaf Olivier nog twee andere voorbeelden om zijn statement duidelijk te maken. De conclusie was dat chemische analyse kan gebruikt worden voor het maken van een gefundeerd oordeel in de conservatie-restauratie.

De derde spreker was Griet Blanckaert, docent Atelier CR Schilderkunst. Aangezien de studenten een rapport zullen maken van het object dat ze uitkozen voor de Summer School, heeft Griet, door een checklist te maken, uitgelegd wat er in het schriftelijke documentatierapport van een object zou moeten staan. Zij legde de methodologie uit van het technisch onderzoek van verschillende materialen, van grondlaag tot afwerkingslaag. De materialen die ze heeft besproken zijn hout, textiel, metalen, papier, glas, bot, steen, keramiek, muurschilderingen, polychroom, grondlagen, bindmiddelen, oplosproeven, verflagen en de afwerkingslaag. Ook gaf ze een korte inleiding over de onderzoekstechnieken die de leerlingen tijdens de zomerschool zullen leren kennen.

De laatste sessie werd gegeven door Jan Callier, o.a. docent Erfgoedstudies aan de Universiteit Antwerpen. Hij legde meer in detail uit hoe foto's correct gemaakt worden voor het schriftelijk documentatierapport.

English version

The introduction of the Summer School was given by Caroline van der Star, teacher at the conservation-restoration of the Stone Department at the University of Antwerp. The first lecturer was Nicole Gesché-Koning, Honorary Professor of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Brussels. She gave an overview about the complexity of ethnographic collections.

First Nicole gave a short historical introduction. During the colonial period there was a bloom in the art market of ethnographic objects imported solely for their artistic aspects. At that time the African art influenced the European art and had mostly an artistic, esthetic value. Later the technological and historical values became more important. Social value was mostly left behind, which is a huge difference with Africa or Asia. Now the social system, the people behind the objects become more important in the Western world.

The lack of knowledge of Ethnographical objects in Europe, being totally out of context or even especially for Europe, leads to the misunderstanding of their sacred or symbolic function within their original communities. This causes loss of their identity and damages their integrity.

The challenges within a hyper specialized and globalized world are the reflections on cultural value, the role of heritage within societies searching for their identity, favoring plural approaches, confronting theory and practice and the communication and collaboration with the communities.

“Let us never forget that we preserve objects to safeguard the message they contain and to present them to the public”.

Gaël de Guichen, Special Advisor to the Director General of ICCROM.

After this, Nicole spoke more about conservation-restoration in Africa. Typical for African art is the huge mixtures of materials, what can be a big challenge. After that she explained the difference between a repair and a restoration. A repair is made during the use of the object, when the object was still in its context. A restoration is only carried out in order to preserve the object stored in a museum collection. A restoration gives no extra value to the meaning of the object, but a repair all the more so. The approach is different than the one in the Western world. Think about the well known Japanese repairs ‘Kintsugi’ gold repairs on ceramics, that gave more value and solidity to the object. A repair made in Africa is part of the object and adds value. A reparation involves a technique that was/is only performed by the person that was/is chosen to do the task.

Another phenomenon in Africa are objects, like funeral statues, that are made to degrade after time, which goes against the idea of trying to preserve a museum object for as long as possible. It is important to address to the community the importance of preserving objects in order to learn from them, even the next generations in the community. In general the Western approach, conservation-restoration is not really known in Africa. There are some conservation-restoration training schools, but very few.

Ethnography museum may no more present the tangible heritage without referring to the intangible one.

Next Nicole elaborated on the presentation of ethnographic collections in exhibitions. First she gave a short overview of important changes during time. The first non-European president of ICOM in 1992, Alpha Oumar Konaré launches ‘What museum for Africa?’, In 1994 at the NARA conference the NARA document on authenticity was presented. In 2004 the declaration of Seoul,on intangible heritage emerged. 2006 Sees the Code of ethics for museums and cultural centres and the development of the notion of inclusive (participatory) heritage.

Nicole continued about the challenges Western museum experience by exhibiting ethnographic objects, more specially about the research on context and the history of an object. Missionary archives store a lot of information. But this information is not always correct. Also pictures must be approached with a critical view. Many of those pictures were staged ( a mise-en-scène), just like some movies. Rituals change and videos made for exhibition are sometimes re- enactments of a ritual. Nevertheless those pictures are valuable as a result of the Western thinking of that time.

Another big challenge for museums is restitution. Nicole gave an example of Sweden. In 1991 the Haisla tribe discovered a totem pole of their ancestors in an European Museum, the Ethnographic Museum of Stockholm, Sweden. The totem pole was part of the museum since 1929. The museum, the Swedish people and the Haisla tribe came to an agreement that the original totem pole was given back to the original owners. But a replica was made in Sweden for the museum in the original techniques by the relatives of the Haisla tribe. It is an example of a win-win situation for both sides.

Finally, she gave some examples of museums in Africa.

The Adjarra museum in Benin was an old school. An antique dealer, that sold his heritage and deprived from the local communities became the curator of the museum. It became a museum made by the people for the people. Another museum is the ‘Zebra on Wheels’. Because of the difficulty to go to a museum in the city, a museum was made on wheels. It goes to local communities and stays there for 3 weeks.

Some interesting books and links Nicole gave during her lecture:

- Gaetano Speranza, Objects blessés. La réparation en Afrique, exposition Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 19 juin - 16 septembre 2007. Paris, Musée du Quai Branly, 2007.

- Place du Patrimoine culturel matériel et immatériel de la République Démocratique du Congo sur les Listes du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO, http://whc.unesco.org

- Cultural heritage and local development. A guide for African local governments, http://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/25/

- www.africom.museum/africom-fr./resources/books.html (AFRICOM)

- www.ceroart.org (Conserver, restaurer. Ecrire le temps en Afrique)

After this extensive first morning, several shorter sessions were given in the afternoon.

Olivier Schalm, teacher in chemistry at the University of Antwerp, gave the next lecture about the role of chemistry for assessing and making informed decisions in a conservation process. He started with the life cycle of heritage and the importance of preventive conservation. He gave the different tasks as problem solving, judging, making decisions and taking action and asked if they were intuition or ratio based.

A conservator-restorer can, in an intuitive way, make informed decisions by training and expertise. A chemist is trained to perform tasks by using analysis. Different approach but they can strengthen each other in their decision making process.

Oliver gave an example of indoor quality converting chemical analyses (charts) in judgements (color codes). Those color codes are easier to read in a straight forward way (it says what it is). You don’t need to interpret intuitively anymore. It is only important to decide beforehand what guidelines/parameters to use.

He gave two other examples to make his statement clear.

The conclusion was that chemical analysis can be used to make grounded judgements for conservation-restoration.

The third speaker was Griet Blanckaert, teacher at the conservation-restoration department of paintings at the University of Antwerp. She explained, by making a checklist, what should be in the written documentation report of an object. The students will be making a report of an object that they will work on during the Summer School. She explained the methodology of the technical research of different materials from support to finish layer. The materials she explained are wood, textiles, metals, paper, glass, bone, stone, ceramics, wall paintings, polychrome, ground layers, binding materials, solution tests, paint layers, finish layer, etc. She also gave a brief introduction of what research techniques the students will learn during the summer school.

The last session was given by Jan Callier, lecturer of heritage at the University of Antwerp. He explained in more detail how to make pictures correctly of a museum object for a written documentation report.